|

Price Realized £229,250 ($369,780)

Sale Information

Christies SALE 5106 —

ORIENTAL RUGS AND CARPETS

24 April 2012

London, King Street

Lot Description

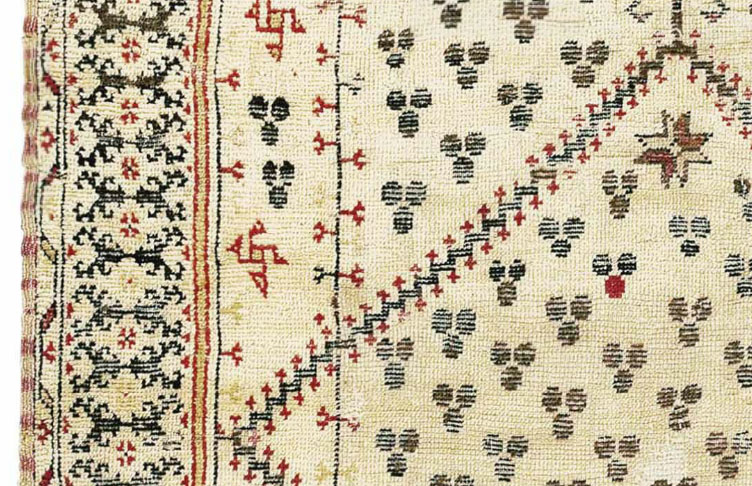

A SELENDI PRAYER RUG

WEST ANATOLIA, LATE 16TH OR EARLY 17TH CENTURY

Uneven overall wear, corroded black with associated repiling, scattered

reweaves and small repairs, selvages original, end kilims mostly original

and secured, backed

5ft.10in. x 3ft.11in. (178cm. x 119cm.)

Provenance

C.H. Boehringer & Sohn, Ingelheim-am-Rhein, gifted on 6 June 1958 to

J.R.Geigy Ltd

Pre-Lot Text

THE BOEHRINGER CINTAMANI PRAYER RUG

Literature

Jürg Rageth, 'A Selendi Rug: An Addition to the Canon of White-Ground

Cintamani Prayer Rugs', Hali 98, May 1998, pp.84-91 and front cover.

Stefano Ionescu, Handbook of Fakes by Tuduc, Boston, 2010, p.130.

Lot Notes

In his study of white ground classical Anatolian rugs and carpets Marino

Dall'Oglio notes that there is a total of about thirty or so white ground

cintamani rugs and carpets of which about twenty five are relatively small,

similar in size to the present rug (Marino Dall'Oglio, 'White Ground

Anatolian Carpets', in Robert Pinner and Walter Denny (ed.), Oriental Carpet

and Textile Studies II, Carpets of the Mediterranean Countries, London,

1986, p.191). Of these over half are prayer rugs which share many features

with the present rug. In his publication of the present rug Jürg Rageth

located thirteen complete and partial examples of which the present rug is

one of the very best preserved (Rageth, op.cit, pp.84-91). The group is

characterized by a restricted palette with overall cintamani field designs

and niches with stepped profiles. In contrast to the 'bird' Ushak and

related rugs with which the present rug shares the palette and basic

structure, none of these rugs appear ever to have been intended for the

Western European export market. None have survived in Western Europe, and

none are depicted in paintings. Also interesting is the fact that virtually

none have surfaced in Turkey; all have an Eastern European provenance and

have generally survived in Transylvanian churches. Ionescu notes that there

is one fragment noted to have come from Turkey (Stefano Ionescu, Antique

Ottoman Rugs in Transylvania, Rome 2005, p.54), and quotes an article by

Alberto Boralevi ('Back To Transylvania', Ghereh 33). He does not however

give a page reference and the quote proves elusive. The popularity of all

white ground Ottoman rugs in a Transylvanian context is demonstrated both by

the fact that Hungarian and Transylvanian inventories from the late

sixteenth century onwards refer specially to "white rugs", and by the

proportion that survive today in Protestant churches there (Boralevi, op.cit,

p.17).

This prayer rug was most probably woven in Selendi, near Ushak in West

Anatolia, where there appears to have been a workshop from which many of the

white ground cintamani prayer rugs originate. This theory is supported by

Halil Inalcik's research into Ottoman price registers (Halil Inalcik, 'The

Yuruks', in Pinner and Denny op.cit, pp.39-65 esp.p.58). In an Ottoman

listing of rugs, their designs, origins and maximum prices dating from 1640,

one entry under the section Seccade (Prayer Rugs) reads: Selendi style with

leopard design. For further discussion on the use of cintamani in the

decorative arts please see Gerard Paquin, 'Cintamani', Hali, no.64,

pp.104-119.

This rug is unusual for its tripartite division of the field, a feature only

seen elsewhere in one largely rewoven rug in the National Museum of Art in

Bucharest (Ionescu 2005 op.cit., no.49, p.105; Rageth, op.cit., no.14,

p.91). The drawing of the prayer arch on the Bucharest rug however is

completely within the restored section, indicating that the present rug must

have served as the model for the restorer, very possibly Theodor Tuduc when

he wove the repair. The majority of the thirteen cintamani prayer rugs also

share the same border as is found here, with minor variations. It is a

border that is only found on one other rug, a Lotto variant rug formerly in

the Wilhelm von Bode Collection (Rageth, op.cit, pl.8, p.88).

Despite extensive enquiries which he details in his article Jürg Rageth

could not track down the provenance of this rug prior to its ownership by

Boehringer in 1958. Ionescu notes that it was previously in a Protestant

Lutheran parish and then in the possession of Theodor Tuduc, but does not

quote the source (Ionescu, 2010 op.cit., p.130). Boehringer was a renowned

collector of art, and a great Oriental rug enthusiast, and it seems likely

that the prayer rug was a personal gift to a particular partner at Geigy.

Photographs of Boehringer's collection are still held in the archive of the

Museum of Islamic art in Berlin, although sadly the cintamani prayer rug

does not appear. The rug was rediscovered in 1995 after a long period when

it was not appreciated; it was cleaned and re-backed at that time. It is one

of only two rugs of this group that are in private hands.

This rug was sampled on 15 March 1995 by Dr Georges Bonani of ETH-Zurich,

sample no.ETH-14055. The C14 results indicated a calibrated age of 1455-1647

with 100 probability.

|