|

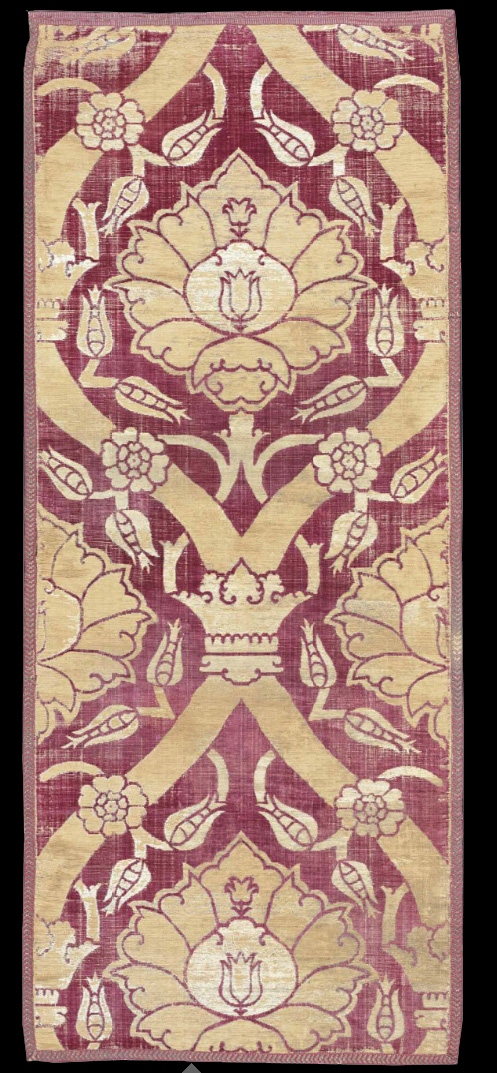

AN OTTOMAN SILK VELVET AND METAL THREAD PANEL

BURSA OR ISTANBUL,

TURKEY, FIRST HALF 17TH CENTURY

Price Realized £11,250 ($18,113)

Estimate £10,000 - £15,000 ($16,110 - $24,165)

Sale Information

Christies SALE 5708

ART OF THE ISLAMIC AND INDIAN

WORLD

4 October 2012

London, King Street

Lot Description

AN OTTOMAN SILK VELVET AND METAL THREAD PANEL

BURSA

OR ISTANBUL, TURKEY, FIRST HALF 17TH CENTURY

The red velvet ground

with silver and gold ground palmettes within ogival lattice strapwork

linked by crown motifs and filled with hatayi flowers, the medallions

circled by vine issuing tulips and further rosettes, in later applied

chevron-patterned border, backed with hessian with four hanging loops

60 x 25¼in. (152.4 x 64.2cm.)

Pre-Lot Text

PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF THE LATE D. LUIS BRAMÃO

Lot Notes

This impressive velvet combines elements imported from

Italian textiles with motifs that are recognizably from the Ottoman

decorative repertoire of the 16th and 17th centuries. A velvet in the

Louvre, catalogued as 'Italian manufacture for the Ottoman market',

provides a likely precedent for the group of textiles to which ours

belongs (inv. MAO 932, Istanbul, Isfahan, Delhi. 3 Capitals of Islamic

Art. Masterpieces from the Louvre Collection, exhibition catalogue, 2008,

no. 12, pp.105-06). It is similarly decorated with large palmettes

contained within an ogival lattice linked by crowns.

It is likely

that textiles bearing crowns, with their association with royalty, were

sent as gifts to the Ottoman palace, appreciated by the Sultan, and

subsequently commissioned locally. Of note is that one of only two

cut-velvet imperial kaftans to have survived in the Topkapi Palace

collections bears an almost identical design, supporting this royal

suggestion (N. Atasoy, W.B.Denny L.W.Mackie and H.Tezcan, Ipek. The

Crescent & The Rose, London, 2001, fig. 88, p.136). That is dated to the

first half of the 17th century.

A miniature from the second volume

of the Hünername, written in honour of Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent by

the writer Seyyid Lokman, which depicts Sutlan Süleyman hunting at the

Filibe (Plovdiv) palace shows two important aghas of the Has Oda, or Privy

Chamber, wearing kaftans clearly patterned with medallions joined by

crowns. They are the çuhadar (in charge of the sultan's outer garments)

and the silahdar (sword-bearer) (3 capitals of Islamic Art, op. cit.,

p.105). Similarly in the Kiyâfetü'l-insâniye fi email-I Osmaniye (Human

Physiognomy Concerning the Person Dispositions of the Ottomans), written

by Seyyid Lokman Ashuri in 1579 and illustrated by Nakka Osman, early

Ottoman Sultans are portrayed in crown-embellished robes (H.1563, David J.

Roxburgh (ed.), Turks. A Journey of a Thousand Years, 600-1600, exhibition

catalogue, London, 2005, fig. 49, pp.270-71). The depiction of such robes

being worn by the highest elite - Sultans and members of the Privy Chamber

that surrounded them - highlights the royal symbolism of the design.

What are plainly Italian elements in the Louvre textile have become

distinctly Ottoman in the present example and in the Topkapi kaftan. The

Italian caper leaves for instance, which are a feature foreign to Ottoman

art (found on a pattern for an Italian textile, dated 1555, N. Atasoy et

al, op. cit., fig. 37, p.183), have here become familiar tulips. An

Ottoman velvet, on green ground, but similarly worked with a lattice

linked with crowns, is in the Keir Collection (B.W.Robinson (ed.), Islamic

Art in the Keir Collection, London, 1988, no.T56, pp.105-06). That example

is dated to the mid 16th century but in the fussiness of the design bears

closer resemblance to the Italian precursors than does ours. Closer to

ours are two panels in the Sadberk Hanim Müzesi, dated to the second half

of the 17th century (Hülya Bilgi, Çatma ve Kemha. Ottoman Silk Textiles,

exhibition catalogue, Istanbul, 2007, no. 21, pp.66-67). Those examples,

like ours, shows the development of the design which has simplified and

become even more recognizably Ottoman. Other similar panels of hatayi

palmettes with four crowns on a lattice are in the Abegg-Siftung,

Riggisberg-Berne (inv.no.2213); Bargello Museum, Florence (inv.no.103F);

Musée Historique des Tissus, Lyon (inv.no.27.887); Royal Ontario Museum,

Toronto (inv.no.972,415.222, a fragment) and Benaki Museum (inv.no.3812).

A liturgical vestment formed of çatmas with crown motifs is in the Lublin

Museum of Ecclesiastic Art in Poland (Nevber Gürsu, The Art of Turkish

Weaving. Designs through the Ages, Istanbul, 1988, no.72, p.91).

So

striking is the design that in the 19th century, a closely related pattern

on a textile, of a palmette with two crowns, served as the model for the

Scottish carpet and textile manufacturers Alexander Morton & Co. An

example of this is in the Art Institute of Chicago (Ada Turnbull Hertle

Endowment, inv. 1988.106). |