|

AN IMPORTANT MONGOL EMPIRE WOOL FLATWOVEN CARPET

CENTRAL ASIA OR CHINA,

LATE 13TH OR FIRST HALF 14TH CENTURY

Price Realized $900,135

Estimate ($747,000 - $1,045,800)

Sale Information

Christies SALE 10374 —

ORIENTAL RUGS AND CARPETS

21 April 2015

London, King Street

FEATURES

Lot Description

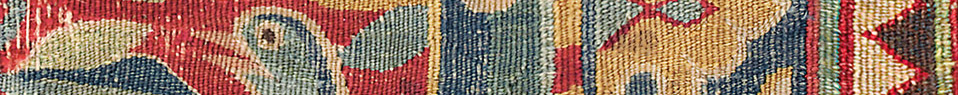

AN IMPORTANT MONGOL EMPIRE WOOL FLATWOVEN

CARPET

CENTRAL ASIA OR CHINA, LATE 13TH OR FIRST HALF 14TH CENTURY

Touches of wear, minor repair, slight loss to each selvage, original long

striped kilim at the top end, secured along the lower end

Approximately

8ft.1in. x 2ft.8in. (246cm. x 81cm.)

Lot Notes

This magnificent

weaving is as mysterious as it is beautiful. It appears to be the sole

surviving example of a Mongol wool tapestry-woven carpet and as such is of

great importance in the canon of Mongol textiles and the history of carpet

weaving.

The only visual record we have of carpets from the Mongol

period is from their depiction in a series of Chinese paintings dating to

the 13th century. The designs of the carpets in these paintings are

clearly discernible and are characterised by strong yet elegant geometric

patterns and a rich palette of red, blues, tans and white (M.S.Dimand and

J.Mailey, Oriental Rugs in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1973,

pp.21-25). These paintings provide a tantalizing glimpse of the designs of

the carpets and context as to how they were used, but raise as many

questions as they answer. In relation to the present lot the overall

effect of the painted carpets is quite different and yet there are a

number of shared design features, such as the palette, the outer stripe of

discs or pearls and the use of lobed cloud band motifs (Volkmar Gantzhorn,

The Christian Oriental Carpet, Cologne, 1991, pp.142-154).

We have

a tantalizing glimpse of earlier simpler flatweave traditions in the form

of a small group of 9th century flatwoven carpet fragments in the Al Sabah

collection Kuwait (Friedrich Spuhler, Pre-Islamic Carpets and Textiles

from Eastern Lands, London, 2014, pp.70-75 and pp.83-85). Many of them

have ends that are finished with a series of stripes, in a very similar

fashion to our carpet. Another very interesting feature is the closely

related structure and selvage configuration, which is most clearly visible

in a border fragment, inv. no. LNS 66 R (Friedrich Spuhler, ibid.,

cat.1.24, pp.84-84). The brindled wool Z2S warps are very closely related

to the present carpet as is the plain multi-cord selvage, which shows

signs of loss but appears to have 7 cords, to the 9 of our carpet. The

palette, the geometric zigzag border and the suggestion of a pearl or disc

minor stripe in one corner all suggest a shared heritage with our carpet.

The border fragment was reportedly discovered in Northern Afghanistan.

This led to Spuhler’s tentative attribution of Eastern Iran as the place

of manufacture but it could just as easily have originated in Central

Asia.

While the border design and structure relates to these

earlier weavings, the field design appears to be from a very different

tradition. It is much closer in both technique and aesthetic to the flower

and bird silk tapestries or kesi of Central Asia and China. It has been

suggested that the technique of those silk tapestries has its origins in

wool tapestry weaving (J.E. Vollmer, Silk for Thrones and Altars, Chinese

Costumes and Textiles, Paris, 2003, p.17). Silk kesi are thought to have

originated with the Uyghurs, a Turkic people originating in Mongolia.

After the fall of the Uyghur empire in the 9th century, we know from the

account of an emissary in the Song Court, Hong Hao (1088-1155) in the

Songmo jiwen (Records of the Pine Forests in the Plains), that Uyghurs

were resettled in Northern Song dynasty territory in modern day Tianshui

in Kansu province and were subsequently relocated to Yanjing, modern day

Beijing, when the Jin Jurchens invaded. Hong Hao relates that some Uyghurs

settled in the Kansu corridor whilst others went further to establish

their own state, in Xinjiang. This narrative creates a fascinating picture

of the dispersal of Uyghurs and their weaving skills across an arc from

the Tarim basin to Beijing and corresponds with areas that we know

produced kesi from at least the 10th century. We know that by the 13th

century the Uyghurs were frequently employed by the Mongols in skilled

administrative positions across the empire, and it cannot be coincidental

that when Ogodei Khan was choosing locations for his resettlement of

weavers he chose the Uyghur capital of Besh Baliq to be one of them.

The patterns and motifs of these Central Asian silk tapestries seem to

have evolved through absorbing and synthesising the different artistic

influences of nearly every major culture that moved along the great

trading routes of the Silk Road. This transmission is well illustrated by

an 11th-12th century silk kesi in the collection of the Cleveland Museum

of Art, inv. No. 1988.100 (www.clevelandart.org/art/1988.100). The

Cleveland kesi depicts a series of three horizontal bands or friezes

depicting floral fields with real and mythical creatures divided by double

borders. The patterns of these borders, a series of multi-coloured pearls

abutting a stripe of bisected alternating lobed flower heads, appear as a

prototype for the border of the present lot and show the influence of both

Sogdiana and Tang China (James Watt and Anne Wardwell, When Silk Was Gold,

Central Asian and Chinese Textiles, New York, 1997, pp.66-67). The

designation of silk kesi to particular regions is however difficult. A

tentative classification of kesi has been attempted on archaeological and

stylistic grounds (James Watt and Anne Wardwell, ibid., p.53). The kesi

that have been identified as Central Asian are characterised by their

clever combination of naturalism and creative pattern-making, exuberant

colours, and depiction of mythical or realistic animals and birds on

floral grounds, all elements that can be seen in the design of the present

lot.

One of the most closely related kesi designs to our kilim is

found in two silk and metal-thread fragments, one in the collection of the

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, inv no. 66.174b, the other in the

collection of the Textile Museum Washington D.C., inv. no. TM 51.61. Both

have very similar drawing to the present lot and are executed in an

interesting mixed technique. The way the treatment of the head of each

bird, defined by an ovoid shape in contrasting colour, with a central

beady ringed eye and clearly defined plumage is very similar to our

carpet. The dynamic and boldly coloured outlines of the design are also

closely related, as are the drawing of the voluptuous and elegantly

swaying peonies and the omission of black from the composition. The

Metropolitan Museum example is attributed to Song Dynasty China (960-1279)

and catalogued as 11th-12th century. Intriguingly, the Asian Art

department of the Metropolitan Museum of Art has confirmed that their

fragment has not been C14 dated. It would be very interesting to see if a

C14 test would bring the dating much closer to that of our carpet, in the

early Mongol period.

The Mongols first invaded North West China in

the early 13th century and over a period of fifty years established the

largest continuous empire ever to exist, spanning from Hungary to Korea.

By 1260 the Mongol empire was loosely organized into four Khanates; the

Yuan dynasty in China and Mongolia, the Golden Horde in Russia, the

Chaghadai Khanate in Central Asia, and the Ilkhanid dynasty in Persia

(Linda Komaroff and Stefano Carboni, The Legacy of Genghis Khan, Courtly

Art and Culture in Western Asia, 1256-1353, New York, 2002, p.16). Whilst

the ruthlessness and destruction of Genghis Khan (r.1206-1227) and his

horde is well documented, what is often overlooked is the importance of

the Mongols in the fostering of the arts and the development of trade

throughout Eurasia almost immediately following the destruction. In spite

of internal skirmishes between the different khanates, the Pax Mongolica,

or Mongol Peace, ensured that foreign merchants and missionaries could

travel from Europe to China in relative safety. It was this active

encouragement of trade under the Mongols that led foreign merchants, such

as Marco Polo, to seek their fortunes in the East by trading spices and

textiles, leading to one of the largest expansions of trade in Eurasian

history (James Watt and Anne Wardwell, ibid., pp.14-15).

Under

Mongol rule, the status of artisans also rose. Genghis Khan freed

craftsmen from corvee labour and relocated many of them from all over the

empire to new areas. Genghis Khan’s son and successor, Ogodei Khan

(r.1229-1241), established at least three settlements of textile workers

in East and Central Asia, one in Xunmalin near present day Kalgan, another

near Hongzhou in Inner Mongolia and a third in the Uyghur capital Besh

Baliq, near modern-day Urumqi in the Tarim basin. Weavers were given

special status due to the importance of textiles for trade, and the Muslim

weavers from Persia were particularly prized for their ability to weave

patterned silks and cloth of gold, nasij (James Watt and Anne Wardwell,

ibid., p.14). The magnificent 14th century Ilkhanid silk and gold-thread

tapestry roundel in the David Collection, Copenhagen, amply demonstrates

why the Muslim weavers were so sought after (Kjeld von Folsach, Art from

the World of Islam in The David Collection, Copenhagen, 2001, fig.642,

pp.376-77 and Kjeld von Folsach, Pax Mongolica, ‘An Ilkhanid

Tapestry-Woven Roundel’, Hali 85, pp.80-87).

The David Collection

Ilkhanid silk and metal-thread tapestry makes a particularly interesting

comparison to our carpet, due to it having been C14 dated to the first

half of the 14th century. The bold colours, the floral and animal

composition, and the incorporation of trefoil motifs in the David

Collection roundel are all shared factors with our carpet. They are design

features that have far more in common with the silk kesi of China and

Central Asia than with known Islamic tapestry-woven textiles. However,

stylistically the drawing of the elegant but highly stylized animals,

birds and figures which relate closely to Ilkhanid metalwork iconography

clearly identified as such by the inscriptions, the inclusion of cotton in

the structure, the figurative composition and the legible Arabic

inscription all suggest that it was woven within the Ilkhanid Empire

centred on Iran.

In her article ‘Textiles and Patterns Across Asia

in the Thirteenth Century’, Yolande Crowe considers the importance of

looking at a range of crafts for evidence of more accurate attribution and

addresses the correlation between ceramic and textile designs (Yolande

Crowe, ‘Textiles and Patterns Across Asia in the Thirteenth Century, A

Southern Song Tomb, Armenian Manuscripts and Mongol Tiles’, Carpets and

Textiles in the Iranian World 1400-1700, Oxford and Genoa, 2010,

pp.11-17). In this way the 14th century blue and white ceramics of the

Yuan dynasty are of especial interest in the consideration of our carpet.

The bold naturalistic motifs and carefully contrived pattern design of

blue and white ceramics such as the magnificent fish jar sold in these

Rooms, 11 July 2006, lot 111 are very similar to the drawing of the

present carpet. In particular the furled lotus leaves and flowers and the

waving grasses are reminiscent of the drawing of our carpet. This raises

the possibility that the carpet may in fact have been woven in Yuan China.

The majority of this flatweave is woven in a standard kilim

technique, with front and back being identical, the different colours of

horizontal weft creating the blocks of colour. This is a very old

technique. A kilim dated to the 4th /3rd century BC was sold in these

Rooms, 5 April 2011, lot 100, contemporaneous with the kilims that were

discovered in the frozen graves at Pazyryk. The example sold here in 2011

and the present kilim not only use the wefts to create the colour, but the

wefts are also bent away from the straight horizontal to create curved

lines which establish a much clearer graphic. The technique used in the

present carpet has considerably more variety. As well as the curved wefts,

in the narrow barber pole stripes a different technique is used, with the

wefts of each alternating colour being carried over on the reverse until

the next time that they are employed, making the reverse appear with loose

lines of free travelling wefts like that of a verneh. Another interesting

feature, which would have added a considerable amount of time to the

weaving process, is the securing of the junctions where the different

colours meet. Where there is a colour change each weft, rather than

returning around the warp, is taken to the reverse and there looped around

the weft from the adjoining colour, ensuring that there is as strong a

join across breaks as there is in the solid blocks of colour. This

additional technique makes the weaving considerably more stable,

protecting the kilim from damage by preventing the weaving from opening up

where colours change.

The carpet is in remarkable condition for its

age with wonderfully rich and fresh colours. Despite some loss to one end,

the design of the kilim reads as a complete weaving and it is tempting to

argue that, if it was meant to be hung on the wall of a building tent or

as a door flap, you would not expect it to be much longer than its current

246cm length. This theory would appear to be supported by the transition

across the length of the design from the two doves sitting amongst the

grasses and watery lotuses at the bottom of the kilim to the two large

peonies above it reaching for the sky. This extremely important and

beautiful weaving sheds new light on textiles of the Mongol Empire and is

a new milestone in the history of carpet weaving.

|